The Canal in Medina

The “new paradigm”

In 2015, the Sevillian publishing house Libros de la Herida published Tartessos. Un nuevo paradigma (Tartessos. A new paradigm), where I propose and point out a specific location as the site of the legendary city that the Bible calls “Tarshish” and the classical Greeks call “Tartessos”, a material and cultural emporium whose location is today, according to some experts, the main challenge facing Iberian archeology.

The existence of that city is accredited in indisputable historical texts, and its antiquity is proven by the place it occupies in the very genesis of Greek myths (Elysian Fields). It is even known with certainty that it was in the Andalusian Atlantic area between Gibraltar and Guadiana River, although its specific site has not yet been located.

To understand the relevance of this name in ancient history we must remember an essential fact: the European continent was divided for many centuries between a Mediterranean maritime area that used writing, and an Atlantic one that did not. These two worlds did not mix or even communicate; in the 5th century BC, Herodotus expressly stated that he never met a visitor from the ocean.

The effect of this dichotomy is that although we know in some detail what happened among the ancient European Mediterranean peoples, of the Atlantic ones we only know what we can deduce or assume from their archaeological remains. This is how the interest in Tartessos is understood: it is the only reference that the Mediterranean texts transmitted about the Atlantic peoples, inhabitants o the world “beyond the Pillars of Hercules”. The only “historical” reference, because from those same times comes to us a second reference to another Atlantic city, although this one has a legendary or mythical character. We speak of Atlantis, as described by Plato in his Dialogues. And since we only know these two references, it seems reasonable to suppose that both, the historical and the legendary ones, could have alluded to the same reality.

Herodotus states that the Greeks reached Tartessos twice. The first one accidentally, at the end of the 7th century BC; the second one, officially invited by their king Arganthonios, in the middle of the following century. There is no record of the Greeks visiting any other Atlantic city, so Professor Adolf Schulten proposed last century that Atlantis was a Platonic fabulation of the much starker reality of Tartessos. And to the best mythographers of his time, such as Jessen or Hennig, Schulten’s proposal seemed to be the egg of Columbus.

The same good reasons that Schulten put forward a century ago for identifiying Tartessos = Atlantis will continue to be so tomorrow. It seems possible that Plato came to know the description of Tartessos made a century earlier by the Greek embassadors invited to the kingdom of Arganthonios, and he based his Atlantis on it. In order to disguise it, he would have fabricated it by exaggerating his data in order to make them implausible. It is the case when he describes the treasure in Atlantis temple (which has attracted so many treasure hunters century after century!) or when he explains in detail the incredible magnitude of the canals that surround the capital. The existence of large canals is one of the characteristic data of Atlantis.

The hypothesis of my approach is the result of a long immersion in the historical sources, especially in the extensive poem entitled Ora Maritima (The shores of the sea) by Rufus Festus Avienus, the decisive text on Tartessos. This work, thoroughly analyzed by Schulten a hundred years ago, was printed in Venice at the end of the 15th century based on a 5th-century Latin manuscript that in turn translated an anonymous Greek text from the middle of the 6th century BC, so the information it contains has leapt two and a half millennia to reach us: the poem was composed 26 centuries ago, translated into Latin 16 centuries ago and published as an incunabulum 6 centuries ago.

It describes a coastal journey between Marseilles, which was then a Greek colony, and Tartessos, a city in southern Iberia, with the drawback that the geographical features have, of course, different names from the present ones. In addition, the distances that separate them are expressed in days of navigation (one day’s journey). The average magnitude of such journeys has been unknown until the appearance of this book, where I have managed to establish it at 90 nautical miles.

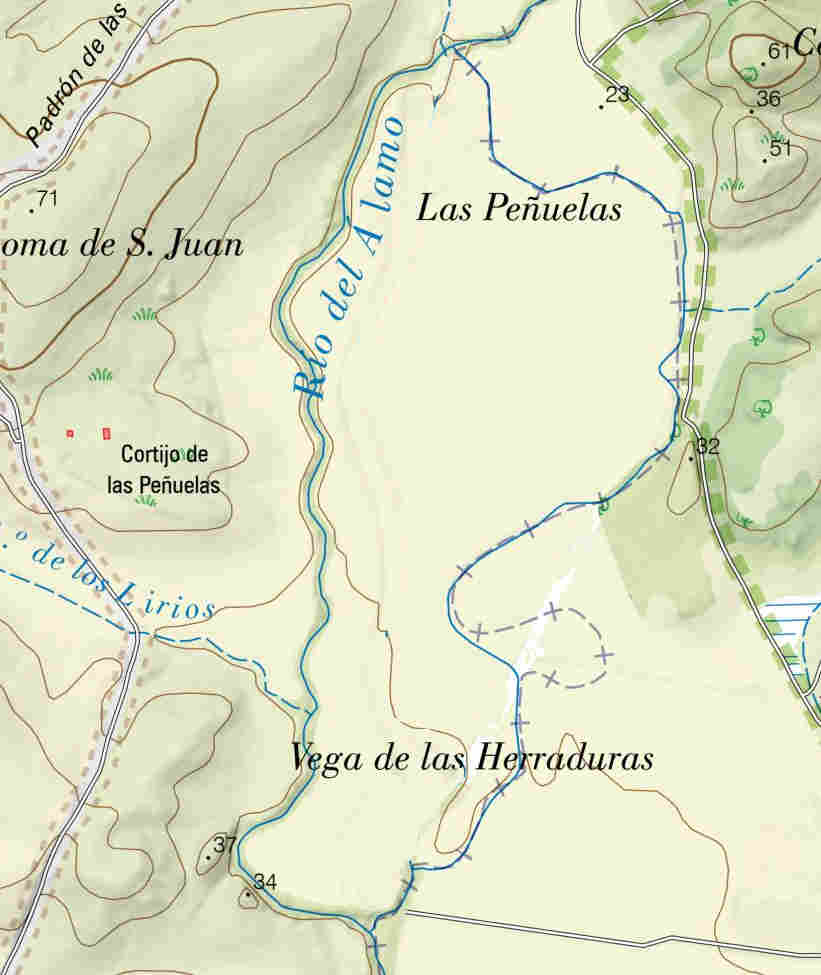

From this data it has been possible to identify the western limit of Tartessos (Cape Saturn) with Cape Trafalgar, as well as to match the river that flows at its foot, which the Greek poem calls Hiberus or Tartessos, with the current Barbate River. Going upstream above the point where it receives the flow of its three eastern branches (from this point on, it takes the name of Alamo River), the indications of the old poem lead to an interfluvial plain in the municipality of Medina Sidonia, an island between the two branches in which the Alamo River opens and closes again a kilometer and a half further downstream.

This naturally defines an area of 1,500 m in length and 800 m in maximum width that I have called “Island H”, which would correspond both to the site of the city mythologized by Hesiod (the Island Erytheia of Geryon, that of the Elysian Fields), as well as to the first western kingdom recognized by Herodotus: Tartessos, ruled by Arganthonius.

The new paradigm established from the distance covered in a day´s journey coincides territorially (in other ways) with the hypothesis of the Dutchman Abraham Ortelius, considered the most illustrious cartographer of his time. The coincidence between both hypotheses can be seen in one of his great historical maps, Hispaniae veteris descriptio, made in 1586 by order of Philip II, in which he inserted (right corner) the detailed profile of the coast from Cadiz to Gibraltar:

Ortelius, whose holographic copy of Ora Maritima is preserved in Leyden, places the “arganthonian plain” or ARGANTONINI campus behind Trafalgar his Iunonis Promontorium.

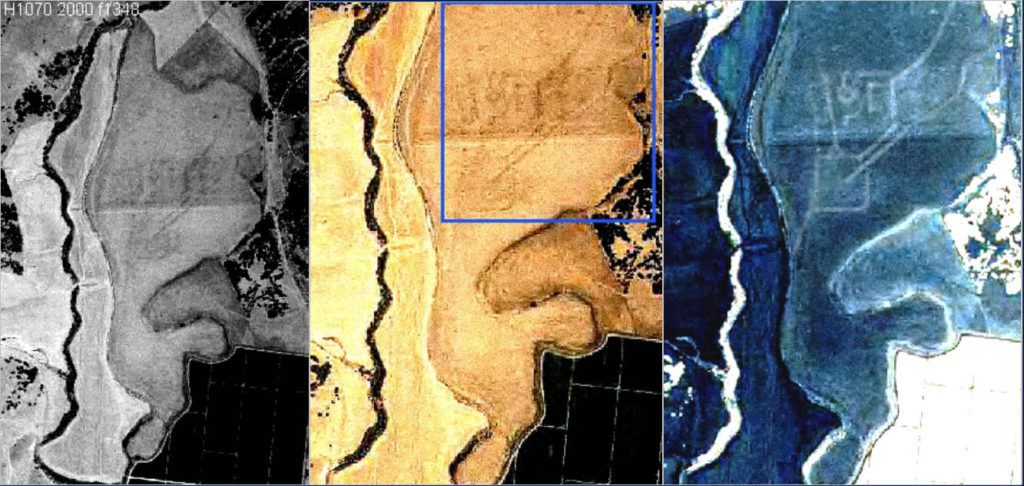

Un nuevo paradigma also provides an aerial photograph of the Island H corresponding to the flight made by the National Geographic Institute (NGI), in which an enigmatic set of shadows that never cross each other can be seen. The shadows are accentuated with successive color shifts until they define parallel lines and orthogonal profiles. Despite my skepticism about aerial photography as an aid to archaeological practice, I must admit that the shadows in the photograph in question are geometrically coherent. Their measurements can be estimated based on those of the square placed to the south, whose side measures about 130 meters.

2: Geophysical prospecting.

In 2019 the municipality of Medina Sidonia managed to get the ground penetrating radar (GPR) of the University of Cadiz (UCA) to carry out a geophysical survey in the interfluvial area of the Island H.

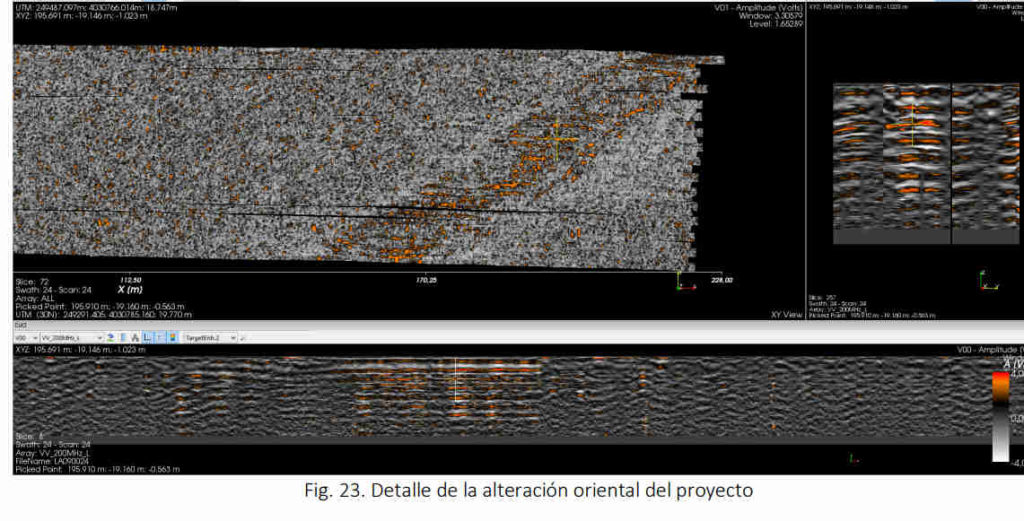

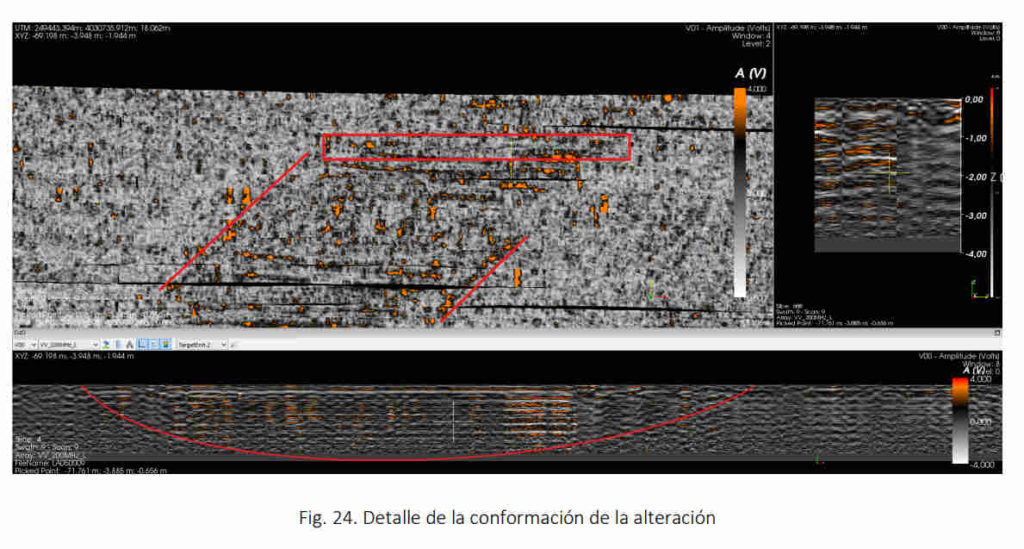

This survey reveals the existence of two anomalies in the subsoil. The first one is an old canal, now completely filled up, which corresponds to a sector of the photographic shadows of the 2000 flight and extends beyond the limits of the surveyed area:

In addition, the graphs accompanying the report show that the detected excavation follows a constant rectilinear direction and that its banks are regularly parallel, very well marked and delimited along the entire length surveyed. The UCA report considers that we are dealing with an ancient canal whose edges show linear alterations, and states with extreme scientific prudence that it shows signs of having been anthropically intervened.

To put it simply: the survey reveals the physical existence of an old canal, now filled up, whose banks seem to have been garnished or paved (?). And this is where the CGN 2000 aerial photo shows a shadow line that goes up to the eastern branch of the river and stops a little below the surveyed area. In that photograph the surveyed area is defined by the red quadrangle, and the recognized cannal section is defined by the series of yellow dots. The rest of the shadows that should have been recorded by the prospector according to the photograph do not appear, but given that the brevity of the report does not facilitate the position of its limits, the only thing we can say is that what was found is part of a much larger continuum of shadows. Thus, we are not only faced with a buried cannal: we are faced with the disturbing possibility that the rest of the shadows with which the segment of the cannal now discovered forms a coherent whole, were also the work of man.

The magnitude of this ensemble, which could be understood as a system of canals, can be judged from the known fragment, which has astonishing dimensions: 24 m wide by 3 m deep. The shape of the canal’s bed that the UCA report presents in the lower part of the graph, is remarkably regular, although it seems to show a more gentle rise in the eastern part of the canal.

There are no canals of this size known in Spain. The average depth of the Canal de Castilla, designed to be navigable between Segovia and the Bay of Biscay, is less than two meters, and its width ranges between 11 and 22 m maximum. The canal that has been discovered in Medina is so large that in 100 linear meters of its bed 20 houses of one floor and 100 m² of surface area could be buried next to each other. Given that it is only a segment of the set shown in the aerial photograph of the National Geographic Institute, we could be looking at a system of canals of unusual magnitude.

The finding itself raises several successive questions, the first of which concerns its origin. The report of the UCA ventures the hypothesis that it could be a natural channeling that runs between the Alamo stream and the other river branch. However, its own morphology (the straightness of its course and the constant width between its banks revealed by the graphs) clearly points to a human origin. Nevertheless, the possibility that the 24 m wide and 3 m deep canal was dug to join two streams whose beds are only one-sixth as wide and half as deep seems absurd.

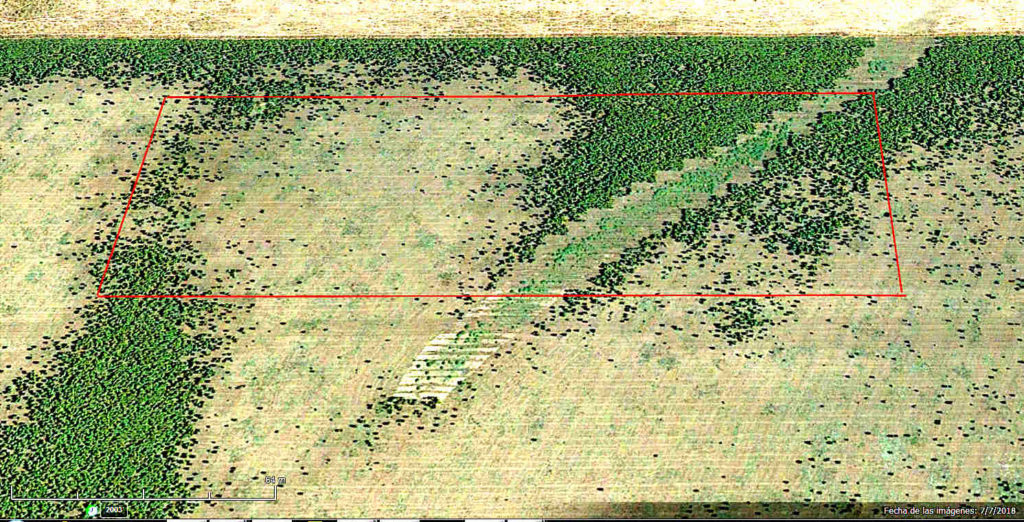

In addition, it is necessary to consider the remarkable linear alterations on its banks mentioned in the report, whose presence and regularity rule out the natural origin of the anomaly. Whatever they are, these alterations exist: there is something on the edges of the canal that is not only detected by geophysics, but also by the growth of flora on them. This is how convincingly it is expressed in the 2018 Google photograph on the surveyed part of Island H (red rectangle), where cropmarks are regularly shaped as a stair on the edges of the canal:

There is another reason to rule out the possibility that it is a natural paleocanal, whic is that the canal does not connect with the other branch of the river that closes the island to the west. In fact, it is a blind canal that is interrupted 50 m south of the surveyed area, as can be seen in the photograph above, accessible on Google during the geophysical survey, and also in this enlargement below. It is obvious that the canal ends abruptly, so that there could never have been a current that could have excavated it.

The series of successive horizontal bands of lighter coloration in the previous image are not understood either. All of them are in the range of 2 m of mean latitude, with a length that decreases progressively from 20 m for the upper ones to 12 m for the one that closes the canal. As can be seen, these clear strips occupy the entire width of the canal following its banks linearly, so that in this final part there is no hint of steps, unlike what we have seen in the upper section.

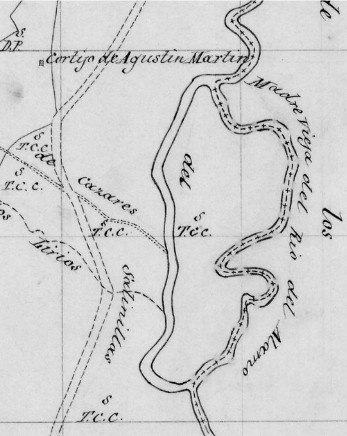

The Island H c.1870

Regarding the time when the canal was dug up, it can only be said that it is not modern. It is completely filled up with sediments, a natural process that, given the magnitude and depth of its bed, would necessarily have taken many years or centuries. No record or memory of its construction have been found and, finally, the oldest map (c. 1870, left) on which Island H appears does not show the slightest indication of the canal now detected. Only its excavation will allow to date it with any certainty after analysis of its banks, where the GPR found the aligned anomalies and Google photographs show the unusual cropmarks shaped as a stair.

Also enigmatic is the purpose for which it was made. Its dimensions rule it out as a diversion ditch between the two branches of the river, for which a channel one meter wide and one meter deep would have sufficed. Conversely, the Medina excavation would have required enormous efforts. With such dimensions, each linear meter of advance would mean moving about 40 m3 of materials, about 65 metric tons. This is a collective work as colossal as it is inexplicable.

3. The second anomaly: the trenches.

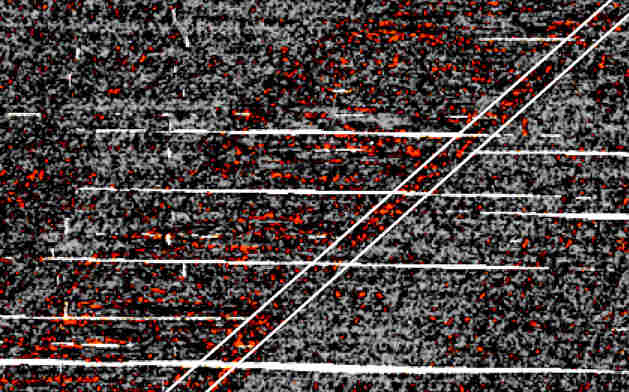

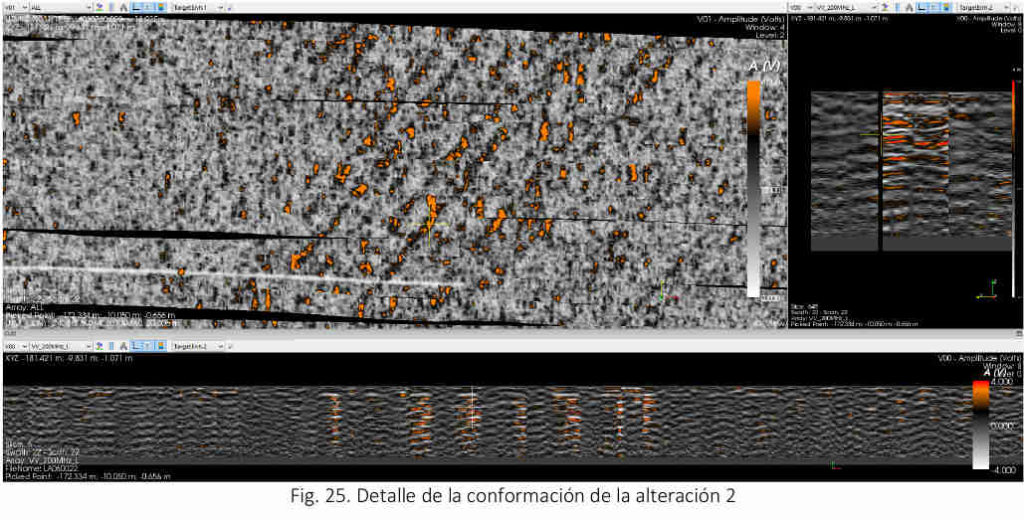

The second anomaly recorded in the area by the UCA GPR team is no more explicable. About 70 m to the west of the canal and parallel to its bed, the radar located a series of at least 20 parallel trenches separated two meters from each other, with a length of around 100 m each, although they continue to the north and south of the surveyed terrain (below).

The trenches are also filled up. They start half a meter below the current ground level and end two and a half meters below. However, they are only 40 cm wide, which raises the question (not a minor one) of how they could have been excavated when they are less than the width of a normal excavator’s torso.

From the fact that both anomalies run parallel, a common explanation could be deduced: they may have had a defensive purpose. The trenches would have constituted an insurmountable obstacle for cavalry, and the canal for infantry. But in such a case it would be neccesary to deduce that both works were intended to protect something of utmost importance for their hard-working builders. And what was protected could not have been far from their protection.

Alberto Porlan. Contact: nomeuropae@yahoo.es